- Sun 26 July 2015

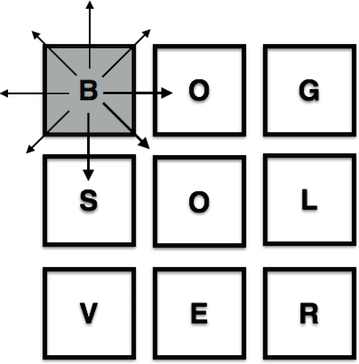

A few weeks ago I found myself in a bar playing Boggle with my fiancé (spoiler: she won). As we drank and played into the night, we wondered just how many different word combinations were possible on a given Boggle board (our estimations were pretty terrible given the aforementioned drinking). Some quick google-ing found the answer1, but it got me thinking: I should totally write a program that solves a Boggle board2.

My first attempt

Using Ruby, I created a board represented by a multi-dimensional array containing N x N squares. The board object also held the running word count, the word list, and the dictionary used to validate a word. My very basic algorithm:

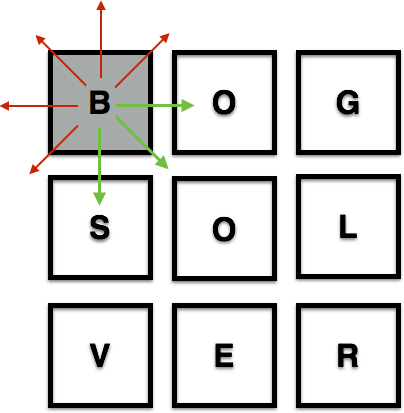

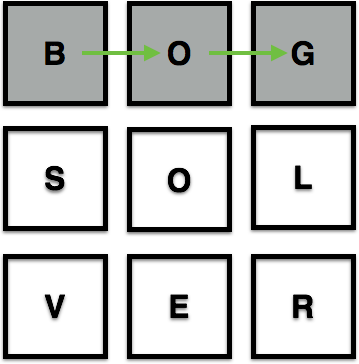

1) For each square on the board (starting in the top left corner), attempt to move every possible direction until you make an invalid move:

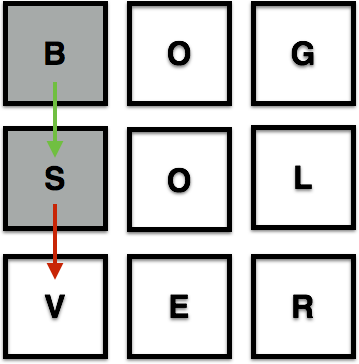

2) Invalid moves occur when the move runs into a wall:

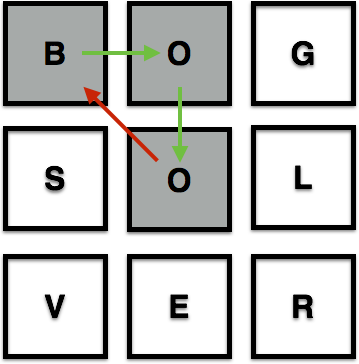

when the move runs into an already used square:

and when the move does not make a word or a potential word e.g "b-o-o" is a potential word, "b-s-v" is not:

3) If a sequence of blocks greater than 3 creates a valid word, add that word to the word list:

4) Continue until all squares and directional moves have been attempted.

The board object's dictionary is stored as a hash. To check whether a potential character sequence is a word, I iterated through each key of the dictionary hash, and checked whether the key contained the character sequence using the ruby "starts_with?" method.

def potential_word?(dictionary, current_word)

dictionary.keys.any? {|k| k.start_with? current_word.downcase}

end

This worked fine when I tested the function on a 3 x 3 board. When I tested it on a 4 x 4 board, the function took a minute to return a result. On a 5 x 5 board, the function never returned at all3. Every time the function looked into the dictionary to see whether a character sequence was a potential word, the program searched the entire dictionary up to that word. While this was okay for the word "apple", it was unacceptable for "zebra". And while solving a 4x4 board in under a minute is good enough to beat the clock in a standard game of Boggle4, but I was pretty sure I could do better – enter the Google.

Giving Boggle a Trie

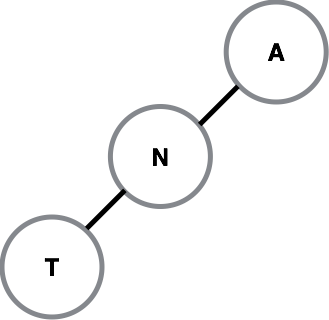

I stumbled upon a few pages5 describing a structure called a trie (prounounced 'try' or 'tree'). A trie is a type of tree6 whose roots are the first character of a word, with successive letters of the word becoming the branches and leaves of the trie. I7 think of it as looking something this:

To build a trie from an array, the algorithm starts with an empty hash (h = {}), and sets the function's position at the very top of the hash. It then looks at each character in the first word of the array – if the hash contains that letter, the position is updated to that hash value h = h[char]. If a character (char) is not currently in the hash, that character is added to the hash with an empty hash as its value e.g.

h = { char=>{} }

This is definitely one of those easier shown than said data structures, so let’s look at an example. If we had a very short dictionary of words beginning with the letter ‘A’, it could look something like this:

[ant, and, abs]

and our starting hash would be empty:

h = {}

To create a trie from this list, the algorithm would start with an empty hash, h = {}, and begin with the first letter of the first word in the list (‘ant’). Is there an ‘a’ in our hash? Nope. So the algorithm adds the character ‘a’ to the hash with a default value of of empty hash, making our hash look something like this:

h = { a=>{} }

The position of the algorithm is adjusted to h[‘a’], meaning that any new nodes added to the trie will occur on the 'a' node. This represents the algorithm “traversing” the trie downward. When the algorithm looks at the next letter(’ant’) in the first word, it again finds that the letter is not present in the hash of the current position, so ’n’ is added to the hash at its current position, h[‘a’], which is an empty hash {}. The hash (h) now looks like this:

h = { a=>{ n=>{} } }

This nesting continues to the end of the first word (’ant’), creating a nested hash that look like this:

h = {a=>{n=>{t=>{}}}}

Using our previous tree-esque visualization, the trie would look something like this:

Moving on to the second word (‘and’), we begin the same process, looking to see if the first character ‘a’ is in our hash. This time, the answer is yes. Therefore, instead of adding the first letter to the hash, the algorithm traverses down the trie, setting its position equal to h[‘a’], with the hash remaining unchanged. The same thing happens when we get to the next letter, ’n’ — the position is updated to a[’n’].

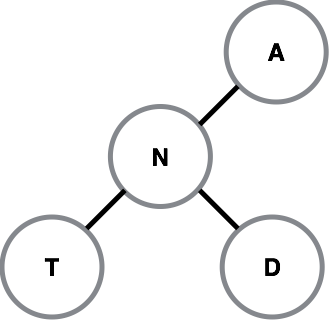

On the final letter of ‘and’, a new node is created because the letter ‘d’ is not included at the hash position a[’n’]. We now have a hash that looks like this:

h = {a=>{n=>{t=>{}, d=>{}}}}

When we add the full list, we end up with a hash that looks like this:

h = {"a"=>{"n"=>{"t"=>{}, "d"=>{}}, "b"=>{"s"=>{}}}}

So why does this matter?

When traversing an array or a dictionary to check whether a string of letters is part of a valid word, the algorithm would have to look at each letter of each word until it found a match (in a dictionary) or a letter that indicates you’ve passed the word (in a sorted array). That means in a game of Boggle, each time my original algorithm looked to see whether a potential word that begins with B is part of a valid word, it would have to look at every ‘A' entry in the dictionary. This gets expensive8 when you’re looking at words that begin with X,Y, and Z.

With a trie, we only look at the letters we have to. Using a trie data structure, the maximum amount of time the algorithm takes to figure out whether a string is a potential word relates to the length of the potential word, and not the size of the dictionary. Using O-notation, the trie is said to have O(N) complexity (worst case), where N is the length of the word.

My original algorithm had a much less favorable worst-case time complexity, something along the lines of O(Σ(M)), where Σ(M) is the sum of the lengths of each word in the dictionary9. Because the sum of the lengths of all the words in the dictionary is much much longer than any one word in the dictionary, my original algorithm takes a much longer time to run vis-à-vis the trie implementation.

Using this new implementation, solving Boggle boards is a breeze. I just ran a 5x5 Boggle board and a 50x50 Boggle board, with the solutions clocking in at 2.5 and 12.0 seconds respectively. Not too bad for a trie.

-

12,029,640, if you're wondering. ↩

-

Because this is what normal people do. ↩

-

I know what my friends are saying inefficient boggle_solver, but I know you'll return one day. ↩

-

A standard game of Boggle uses a three minute timer, as does Big Boggle. ↩

-

In particular this stack overflow page. ↩

-

Which is just confusing. ↩

-

And Wikipedia. ↩

-

Meaning computationaly expensive aka very slow. ↩

-

I think the average complexity would be O(Σ(M)/2) – complexity divided by two because a word is just as likely to appear at the beginning of the dictionary as it is the end. ↩